What Was Thomas Hart Bentons Style of Art 1930s

Thomas Hart Benton

THE MURALS OF THOMAS HART BENTON

In 1932 a set of large wall murals was unveiled on 10 Westward 8th Street in New York City. Information technology was Arts of Life in America - four huge wall panels and four more than around the ceiling. These panels draw the 'Arts' of everyday life - music, games, dance, and sports. They as well show regional multifariousness, unemployment, crime, and political nonsense. They give a comprehensive portrait of life in the 1930's.

A GLIMPSE AT THE 5 MAJOR PANELS

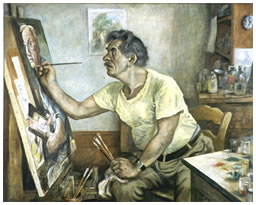

Benton had a fascinating working method, and was a controversial effigy in the earth of mural art, frequently in public conflict with others. He was a pivotal figure in the story of art in America. He was originally influenced by the erstwhile masters of European art, then by modern artists experimenting with brainchild. He turned away from abstraction to paint his own land and its people, becoming a 'Regionalist' painter. As the tutor of the young Jackson Pollock, his influence passed on to the side by side generation of abstract expressionists and can be seen in pop fine art.

Today y'all can run into v of the mural panels at the New Britain Museum of American Art. They were purchased in 1953, and Benton maintained a special relationship with the museum for the remainder of his life.

In addition to the murals themselves, the museum holds 5 preliminary studies for the series and an almost consummate set of Benton's lithographs.

Arts of the City

In 1929 the stock market crashed. The Arts of Life in America was painted at the height of the Bang-up Depression. Roosevelt was campaigning for the White House. Prohibition was the police force of the land. Bootlegging of illegal alcohol was big business organization, especially in the cities.

| Arts of the Due westThomas Hart Benton was born in Neosho, Missouri, and every bit a small male child captivated the life of the western frontier. Although he after spent much fourth dimension in cities (Washington, D.C., Chicago, Paris, New York), he never forgot his rural roots. |

Arts of the SouthThomas Hart Benton took sketching trips by automobile in the 1920s and 1930s through various sections of the land, only it was in 1928 that he discovered the Southward on a trip from Pittsburgh through Georgia and Louisiana to New Mexico. |  |

| Indian ArtsBenton's agreement of the Native American culture was fairly informed, if we evaluate the landscape, Indian Arts. In this work, he chose to portray the Plains Indians and their manner of life, which was past this time only a memory in history. An early lithograph, called Historical Composition, of 1929, conspicuously relates to this mural and may have been the creative person'south first handling of a Native American subject. |

| Political Concern and Intellectual Ballyhoo Benton came from a political family unit. His father was elected to Congress in 1896, and the family alternated residences between Missouri and Washington, D.C. This early exposure to political life stayed with Benton the rest of his life. In the final panel of this series, Political Business and Intellectual Ballyhoo, he makes fun of all forms of politically-charged advice. |  |

Benton soon tired of bookish routines and drifted toward various mod styles, in role through the encouragement of the modernist American painter, Stanton Macdonald-Wright, who became a close friend.

From an early on age Benton showed remarkable skill every bit an artist, a talent his mother encouraged simply which his father deplored, since he wished his son to focus on politics or police force. Notwithstanding Benton persuaded his father to send him to art school in Chicago, followed past farther written report in Paris and New York.

The painter, writer, and musician Thomas Hart Benton was born in Neosho, Missouri, the son of a famous Missouri political family.

Until the early 1920s, Benton was generally viewed equally a modernist and ran through the gamut of modern approaches, such as CÈzannism, Synchromism, and Constructivism. The turning signal in Benton's career came in 1924, when he returned to Missouri to visit his dying male parent, whom he had non seen in years. The talks he had with his male parent and with his father'due south old political cronies filled the artist with a desire to reconnect with the globe of his childhood.

In 1930 Benton produced an enormous mural program, America Today, which received a groovy deal of attention. Information technology was followed in 1932 by the five-part series, Arts of Life in America, the subject of this educational component of the museum's website.

In 1934 Benton's fame was clinched when he was featured on the encompass of Time magazine--an honor never earlier awarded to an creative person. The article in Time linked Benton with two other Midwestern artists, John Steuart Back-scratch and Grant Forest. From that signal on, Benton was best known to the public as the leader of the "Regionalist Movement" in American art, which opposed European modernism and focused on scenes of the American heartland.

In 1935 Benton left New York, where he had lived for more than than twenty years, and resettled in Kansas City, Missouri, assuming a educational activity position at the Kansas Metropolis Art Institute.

In 1941 he was fired from the Institute for making tactless remarks about homosexuals in the Kansas City art world. He remained popular nevertheless until the tardily 1940s, when his work came under attack by European-trained art historians, and abstraction began to capture the attention of leading art critics. Ironically, the about charismatic figure in the new Abstruse Expressionist movement was Benton'southward onetime pupil Jackson Pollock.

In improver to his work as a painter, Benton was a distinguished writer whose autobiography, An Artist in America (1937), became a bestseller. As well a gifted musician, he collected folk tunes, played the harmonica on a professional level, produced a record for Decca, and invented a new form of musical notation for the harmonica that is still used by music publishers.

Benton died in his studio on January 6, 1975, while completing a mural intended for the State Music Hall of Fame in Nashville, Tennessee.

The New Britain Museum of American Art is fortunate to own not just five of the Arts of Life in America murals, but also five oil studies for the murals. Benton as well created clay models of many of the figures shown in the paintings, but these have not survived.

Arts of the West

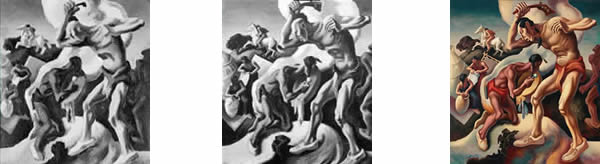

Challenge yourself! Come across if you can find all the changes the artist fabricated between the black and white small study and the terminal wall-sized version in color. For starters, take a look at the tree in the upper left. Then move to the building, the floorboards, and everything else.

Arts of the Southward

Take some time to compare these two images. Why practise you remember the artist started with a small written report using just tones of black and white? Consider the claiming of planning a huge wall landscape like this. How would such a study help? Notice the changes between the study and the final mural - in the distant church, the man on the wagon, and the addition of the lady visiting the outhouse. Now wait for other changes.

Indian Arts

The 2 pocket-sized black and white studies shown here give us a rare opportunity to meet inside the artist's mind. Notice, for example, the cloud that starts from behind the eye figure and ends up in the sky. Notice how Benton plays with its shape and position. See also how the shapes become clearer as he works his mode toward the last large work.

Arts of the City

When Benton enlarged the small black and white study to the final huge landscape, what changes did he brand? Do you meet the lightening commodities that changes to a trumpeting angel? No 1 knows why he did this. Do you accept an idea? Now look at the movie screen. How does the audition watching the movie change in the last version? What other changes practice you run across?

The Benton essay is a rare opportunity to read an artist's thoughts on his piece of work at the time it was made public.

ARTS OF LIFE IN AMERICA

A Series of Murals past Thomas Benton

The Museum Reading room containing these murals will be open to the public during museum hours from dec sixth through 13th 1932. Thereafter the murals may be seen by special appointment.

The proper noun of a motion-picture show, like the proper name of a person or a book, does non reveal the significance or even remotely indicate the combination of factors which establish the reality beyond the name. Names are tags which enable us to roughly locate and separate things. It is easy to forget this fact and to assume that in naming a thing we also know information technology; besides it is like shooting fish in a barrel to allow a name to take the place of a thing and to ready our judgments on exact suggestion alone.

The subject-matter of this Whitney Museum wall painting is named "The Arts of Life in America" in contrast to those specialized arts which the museum harbors and which are the outcome of special conditioning and professional management. The tag is not accurate. On the one hand, it is not inclusive plenty, and, on the other, a point or two would accept to exist stretched to consider every bit arts some of the things represented. The Arts of Life are the popular arts and are more often than not undisciplined. They come across pure unreflective play. People indulge in personal display; they drinkable, sing, trip the light fantastic, pitch equus caballus shoes, become religion and even set up opinions as the spirit moves them. These pop outpourings have a sort of pulse, a go and come, a rhythm and all are expressions - indirectly, assertions of value. They are undisciplined, uncritical and mostly deficient in technical ways, but they are Arts just the same. They fit the definition of Art as "objectification of emotion" quite equally well as more cultivated forms.

Only the fundamental to the pregnant of this piece of work cannot be plant in its name. "The Arts of Life in America" is only a tag hung on American doings which I have found interesting. I have seen in the mankind everything represented except the Indian sticking the buffalo. That instance of romantic indulgence is a hangover from Cooper, Buffalo Bill and the dime novels, as in truth is the spirit of the whole panel on Indian Arts. One does not have to exist a boy scout to empathize and forgive this - through romance we Americans provide compensation for what nosotros actually have done to the Indian.

The great painters of the Renaissance in the service of the church building built their pictures around names of religious significance. They started out with a proper noun and suggestion, in and then far as religious meaning was concerned, finished the job.

Really the real subject-matter of these paintings was given past the life, character and environment of the period. Depending upon the painter's habitation, Mary, the female parent of God, was a Roman, a Venetian, a Florentine or a Flemish belle, and the Holy City was architecturally consistent with the local type. The saints were perfectly proficient people, the feminine characters - generally mistresses of the moment - more or less good, and even the grass and the heaven and the landscape revealed local characteristics. The religious Art of the Renaissance pictured the life of the Renaissance. The same may be said of all religious arts except possibly the Byzantine where a hard technique prepare a representational formula. I mention all this mainly for those who have notions virtually the traditional dignity of mural art.

There is precedent for taking the Arts of Life seriously. Information technology deals, as do the cracking religious paintings, in spite of their names, with things found in an artist's directly feel. If religious associations are considered essential, then by reversing the usual naming process, that is by going from the flick itself toward a proper name, possibly the serious person may observe in the local pursuits hither represented the peculiar nature of the American brand of spirituality. Going further, he or she may find a profounder label than mine and brand of this landscape also a religious work ! But all this is yet a picayune apart from the question of real discipline in the work at hand. The "life of the time" is itself merely another name, a tag which allows united states of america to pigeonhole things conveniently.

The real subject of this piece of work is, in last analysis, a conglomerate of things experienced in America: the subject area is a pair of pants, a hand, a face, a gesture, some physical revelation of intention, a sound, even a song. The existent subject is what an individual has known and felt about things encountered in a real earth of existent people and actual doings. But even this final discipline-matter is not pure; this piece of work is non a mere record of experience - of facts seen, selected and recorded. Many other things must enter equally conditioning elements earlier experience is transmitted by Art. These other things are responsible for the form of this mural and some comprehension of their nature is necessary before the work can be grasped in its entirety.

When we listing the Arts we speak of painting as a visual Fine art. We connect it with the act of seeing,only we are liable to forget all that the deed entails. Before the advent of the photographic camera, the notion of independent vision, to which William James gave the name of the"innocent center," was unknown; and painting and drawing, like other forms of significant action, proceeded from knowledge. An artist's representation of a thing was plainly affected past all of his previous experience. He did non know things by the eye alone but by and through touch, utilise and other conditioning factors. That, of course, is the manner he all the same knows things, if he knows them at all. But a short cut has arisen which enables him to present an appearance of things about which he knows nix. That brusque cut is the fob of photographic rendition - the recording of a retinal image. The thought that an artist could rely on pure visual impression had no existence earlier the invention of the camera. Seeing was non separated from its workout accompaniments until a "seeing" instrument was invented which was untouched by the automated entrance of retention. Representation, before the camera supplied a curt cutting, necessarily involved knowledge of the things represented . And with noesis went pregnant.

Many notions about the nature of expression which have grown up with the use of the camera will have to exist abased earlier we can regain an agreement of the Art of painting as it has been historically practiced, before we can once more approach information technology as a correlation of things known rather than as a slit opened on appearances.

The phrase "correlation of things known" is open to misinterpretation and I must make information technology clear that the pregnant of art arising from such correlation has no connection with scientific truth. The painter's meaning is based upon directly knowledge only the relations he sets up between things reach out, not towards truth in the scientific sense, but toward a conception of propriety in relation ships.

The return of modern painters to a archaic stylization indicates a realization of the necessary dependence of satisfactory form on knowledge. This return grew out of a revolt confronting the effort to tie the painting business to that mechanical rendition of appearance familiarized by the camera. Merely it also has deeper implications.

Painters, as a whole, have been at the mercy in late years of a good bargain of merely ingenious phraseology. What they have accepted and said in explanation of their explorations has been oftentimes obscure - a mere exact play on irrelevant and inaccurate naming.

The defoliation of the notion of "visual innocence" with archaic and kid- like directness has resulted from just such looseness. It is assumed that the child and the primitive are without knowledge, that they merely react to impressions and that the straightforwardness of their forms comes from an unconditioned response to experience. As a outcome the return to primitivism has been misinterpreted and through that misinterpretation, painters have been thrown into an indefensible position where they must deny the validity of knowledge, and ready up a pretension to an incommunicable innocence. They are forced to play dual parts in which the activities of the artist are separated from those of the human being exactly as religious "Faith" is separated from the conduct of actual affairs. Withdrawn from the stimulating pricks of reality their art becomes inevitably a convention and their artistry a mere embroidery laid over these conventions - a sort of costume dance.

Primitives and children know things. Though their knowledge may seem odd to us it is yet valid. It is limited in range, it may non tally with the conclusions of a wider feel only psychologically it is just as much knowledge equally that of the civilized, verbally and mechanically trained adult. A child's picture, once he has grown out of the mere explosive play with material, is a picture non of something seen, in the strict sense, but of something known. He knows a gunkhole or a house or a horse and draws information technology with total indifference to the facts of visual perspective. His idea is to represent experience rather than to imitate its conditions. Afterward on the modern child must accept these atmospheric condition into account simply his first endeavour is to become what he immediately knows to hang together within some limited space. The business of making things hang together is his first experience in correlation.

He devises various means of making the many seem one. The charm of children's piece of work lies more often than not in the unexpectedness and emphatic quality of their logical devices. That apparently innate need of the child, the urge for cohesiveness in the materials used to correspond a knowledge of things, must be retained for successful plastic expression. The of import thing in the education of children lies in developing this urge and in providing techniques of spatial relationships which tin can be expanded as noesis itself widens and as the critical kinesthesia (equally applied to the representation of noesis) grows more than acute He will otherwise become, as most modern children of creative leanings do go, a slave to the representation of advent and spend the rest of his days trying to disguise the fact with technical oddities of one sort or some other.

The difference betwixt the development of the modern child and the archaic lies in the conditioning surround. The modernistic kid grows up with things which induce conclusions and actions of a complex nature. His notions of logic are greatly affected, and rightly, not simply by his directly knowledge of things but also by what they imply. His inferences are derived from his experience of what things practice. An aeroplane is something capable of existence known directly, like a stone or a chair, but the nature of that kind of noesis is immensely affected by knowledge of potential functioning. Thus a mass of derivative cognition enters into the trouble of representation which the modern person cannot escape. The primitive, having had no circuitous instruments to increment the accuracy of his conclusions about directly experienced things, goes about correlating them without besides much of this derived baggage.

As a natural result of this, his representations are more readily fitted to logical relationships, and he finds information technology easy to make an aesthetically satisfying story of the earth because there is non and so much contradictory material to be included.

The painter'south message has zero to do with derivative cognition of a scientific nature, with that sort ot noesis which deals with the causal relations of things. What the painter cannot know by straight contact is not his cloth. These direct contacts have references, implications, extending across their immediate beingness, but it is to immediate existence that the painter goes for the stuff with which his processes actually bargain. He selects from what he knows of things, their meaning aspects. These selections, transcribed in line, colour, and mass, are his material. It is with water, the glittering, smooth or broken plane that he deals, non with H2o.But at the same fourth dimension he cannot avoid the implications of cloth, and it is the complication of these implications which establishes the divergence between the modern and the primitive creative person and makes the aesthetic organization of actual modernistic feel so involved an affair.

Art practice depends upon ii kinds of noesis. One kind is knowledge of the use of correlating instruments, such as symmetry and rhythm which is de- rived from a study of historical practise. The other knowledge is the result of attending to the things of direct feel. What a painting has "to say" is wholly dependent on the latter. Its symbolical reference, its meaning, is jump thereto. Its form, its logic, which correlates what is represented, is the issue of instrumental knowledge.

But these two sorts of noesis affect one some other. In the procedure of correlating things directly known, needs arise which cannot exist met with logical devices of the past. The devices are and then modified, more or less unconsciously. Also the direct knowledge represented is inevitably subjected to some distortion as it becomes part of a logical sequence. Experience is not of a logical nature - all integration involves distortion of some sort.

Art is then a abiding play of meaning against course in which the purity of both is sacrificed to unity. But equally Art, unlike philosophy, makes no pretensions to the establishment of "truth"in and by its logic, but is frankly emotional in setting upwards its sequences, its compromises cannot be regarded as testify of weakness. As a affair of fact, the very strength of Art lies in the middle ground where doing is balanced with significant, logic with experience. A successful work is a measure of both. The various logical devices of painting, the sectionalisation of things into planes, the counterpoint of line and plane, the playing of color against color, light against dark, projection against recession, etc., are instrumental factors prepare to the service of unifying experienced things.

Devices of structure are a heritage of successful practise, drawn from a long train of trial and error. Their logic is the logic of carpentry which sets this against that in the interest of cohesion. Such a logic is less unsafe than verbal logic since information technology is conspicuously a manifestly means of simply getting things together. Information technology is nevertheless unsafe for the creative person because information technology may so readily pb to an habitual unreflective sort of practice for its own sake. Once a way is found of getting disparate factors unified, of making them hang together in a picture, it is natural to cling to that way, peculiarly if accomplishment has a professional person aspect. Ane is probable to close the door on further disparities; to make Art an activity divide from unfolding experience.

In view of the nature of this difficulty, it is very easy for the correlating process to assume so vast an importance that its mere office as an integrating tool is lost sight of. Thus logic becomes an stop in itself and the device all of import.

The whole modern notion of "plastic purity" is built-in of the confusion of the device with its end. The loss of the tradition of logical practice during the menstruum when the novelty of the various tricks of photographic rendition held all the involvement of painters has centered a tremendous attending on its revival and much of our mod Fine art has been, therefore, a sort of experimentation with tools. Rationalization has provided such experimentation with meaning. Back of the whole modern business, as indicated in a higher place, was the dissatisfaction with a mere arrangement of appearances and the need of knowing and saying something that was the event of human rather than mechanical response. It came to exist recognized that the artist as camera was not very satisfactory, that in fact he was non fifty-fifty a good camera.

But the return to traditional practice, every bit in the example of Delacroix, seemed to call for purely romantic views, and a disregard of existent experience. This was obviously not a line of true evolution. New kinds of cognition of things could not be made to square with a practice directed to correlating noesis born in a period of flowing draperies and unquestioned, or but moderately questioned beliefs almost the existent pregnant of things. This problem of finding a logical representation of new experience, new knowledge, is all the same the artist's central problem. One-half of his life is spent learning how. What a contrast with Massaccio and Raphael!

In the face up of this difficulty the modernistic has had to brand excuses for his existence.

Unable to make experience fit with logic, unable to chronicle his practice to his environs, finding himself at odds with society, which naturally is not interested in whatever practice apart from meaning, he has made a trivial world of his own and with the help of his literary friends has invented special psychological faculties to provide it with a semblance of reality. In this world he has set up the notion of "purity" as a criterion of aesthetic value, significant thereby that the elements of artistic practice are sufficient unto themselves.

In life, the claim to purity is practically a declaration of impotence. Information technology is a compensatory value, born and reared in some kind of frustration. Prepare equally an ideal to be maintained, it is an indication of defeat.lt tells obviously that the world of experience cannot exist fabricated to coincide with one's ego - that i's notions ot fitness, of logical sequence, are unable to stand in the flow of fact; that ane'due south integrative powers are ineffective in the actual globe. As the need for logic, for cohesiveness, for getting meaningful sequences in the facts of life, seems to be more persistent than whatsoever other psychological factor, the savage assertiveness of direct knowledge is avoided by the "pure." This mural,"The Arts of Life in America," is certainly not a pure work.

Avoiding the proffer of double significant hither, it may readily be seen that no plastic device is used for itself. Practically every course is jump up with implications which take the attending away from purely plastic values. This is deliberate. On the other hand, the form is not directed to specific meaning in a literary sense. The work is not a vehicle for doctrine. It is not a string of exact ideas transferred to plastic cloth.As the implications of things in life vary with individuals, and so will the implications of the things represented in this work vary. ln addition there will be, and quite properly, private interpretations put upon the relations set up betwixt the things represented. Such and such a contiguity will seem true to one, false to another. Why I placed one unit here and another at that place is merely equally often determined by my formulation of effective placement as by its "truth" to life. The "truth" to life in this work is "truth" seen through and modified by the demands of logical sequence. And however, at the risk of exact contradiction, I must say that the sense of "truth" to life backside this piece of work is what seems most of import to me. The whole grade is in its actuality determined by meanings arising directly from feel. The things represented were known in real life and found significant enough to call for representation long before the complete course of the landscape was considered. The concluding form here shown is then an try to integrate units each of which has in itself its ain split up value as a thing, as a true thing, with a meaning of its own.

The conception of perfect sequence is constantly assaulted by the recalci- trance of these units. They can be modified just merely and then much without losing their representational values. As I effort at all times to retain the full representative value of those units, information technology is inevitable that the sequences of the whole mural be subjected to strains more than or less violent.In the interest of representational inclusiveness, the flow of a line is frequently broken,twisted and sent back on itself.As a effect of this, some other line must needs exist treated violently every bit an outset or counter.

From the architect's point of view, all this is, of course, shameful. The cool dazzler of a wall comes down in ruins. For the architect, architecture is a frame for life, and, theoretically at least, what is included in a space should harmonize with those life activities for which the space is designed. Merely the notion of harmony, the directing influence behind decisions determining what goes with what, is highly conditioned by the nature of one'due south interests. While architecture may exist a frame for life, it as well sets upward spaces which may rightly be regarded as frames for the expression of life. The question of abstract harmony, itself a piffling obscure, then gets involved with one of significance and dissimilar individuals will, following the dictates of their interests, ready radically different views.

From the point of view of architectural theory, painting should fix near enhancing the dazzler of architectural form and should be subjected thereto. The painter, as Frank Lloyd Wright says," should work under the baton of the archi- tect." That is, he should let the architect determine what relations exist set between his lines, colors and masses, in society that these make no interference with the effect of architectural structure. This means that significance should exist sacrificed to form - this is what information technology means in the linguistic communication of theory - actually it ways that significance exist subordinated to a convention,for just that which has no challenging qualities of its own can exist without radically affecting its surroundings.

As the fetish of purity must inevitably autumn when life enters, then the purity of architectural form cannot exist maintained when painting enters, unless that painting is and then pallid, so much a convention, that it is unnoticeable. At that place is plenty of painting, of grade, sufficiently conventional to have no marked effect on its environs, but the architect, though he uses it frequently enough, certainly holds it in antipathy. The telephone call for pregnant, for significance, is strong in all men, and even the architect must tire of empty gesture and sickly archaic affectation.

Painting finds its meaning in life and life fits into no resurrected convention. Painting, inclusive of meanings which are the result of real life experience, must build logical structures of its own. Such structures, in and through the meanings they comprehend, set upwards unprecedented properties in the lines, masses, colors, cubes, cones or cylinders to which they may be reduced, and these must affect the alignment of similar factors in architectural class. Painting expresses or represents; but the stuff through which information technology does this is finally reducible to a play of geometric factors. Equally architecture is apprehended aesthetically through the play of similar factors in that location is bound to be reciprocal action between the two Arts when they are joined. Neither can maintain wholly the purity of their values. Part in architecture determines the alignment of cube, cone, cylinder, mass, line and plane. Structure is at the service of purpose, of significant. This is likewise true of painting whose about important office is its social function, the expression of life. The expression of life, tied every bit it is to direct feel, constantly brings new units to painting, because life is e'er changing. These units logically adjusted to one another gear up up their own dynamic geometry which is not the geometry of architectural form considering it has a different origin and part. Compages is built around life activity; painting is built on the expression of that action.

Line, mass and color, the materials of painting, function instrumentally in the interest of unity, geometric unity, only that function is itself greatly affected by the nature of what is to be unified if the final form is to take other than a superficial value - if it is to have meaning. Architectural logic, the builder's formulation of formal fettle must, like the logic of painting, submit to modification under the pressure level of values which are not inherently its own.

The room, on the walls of which this mural is painted, was certainly no builder'south dream but information technology presents, simply the same, a fair example of what painting, which aims to exist inclusive of real significant, may exercise to architectural structure; what to some extent it must e'er practice.

Whether the result is harmonious, whether it bears any relation to architectural function, may set some discussion going, only it is likely to become at last a purely theoretical question which will suffer the fate of all theoretical queries in the face of a "fait accompli."

Thomas H. Benton

Source: https://nbmaa.org/thomas-hart-benton